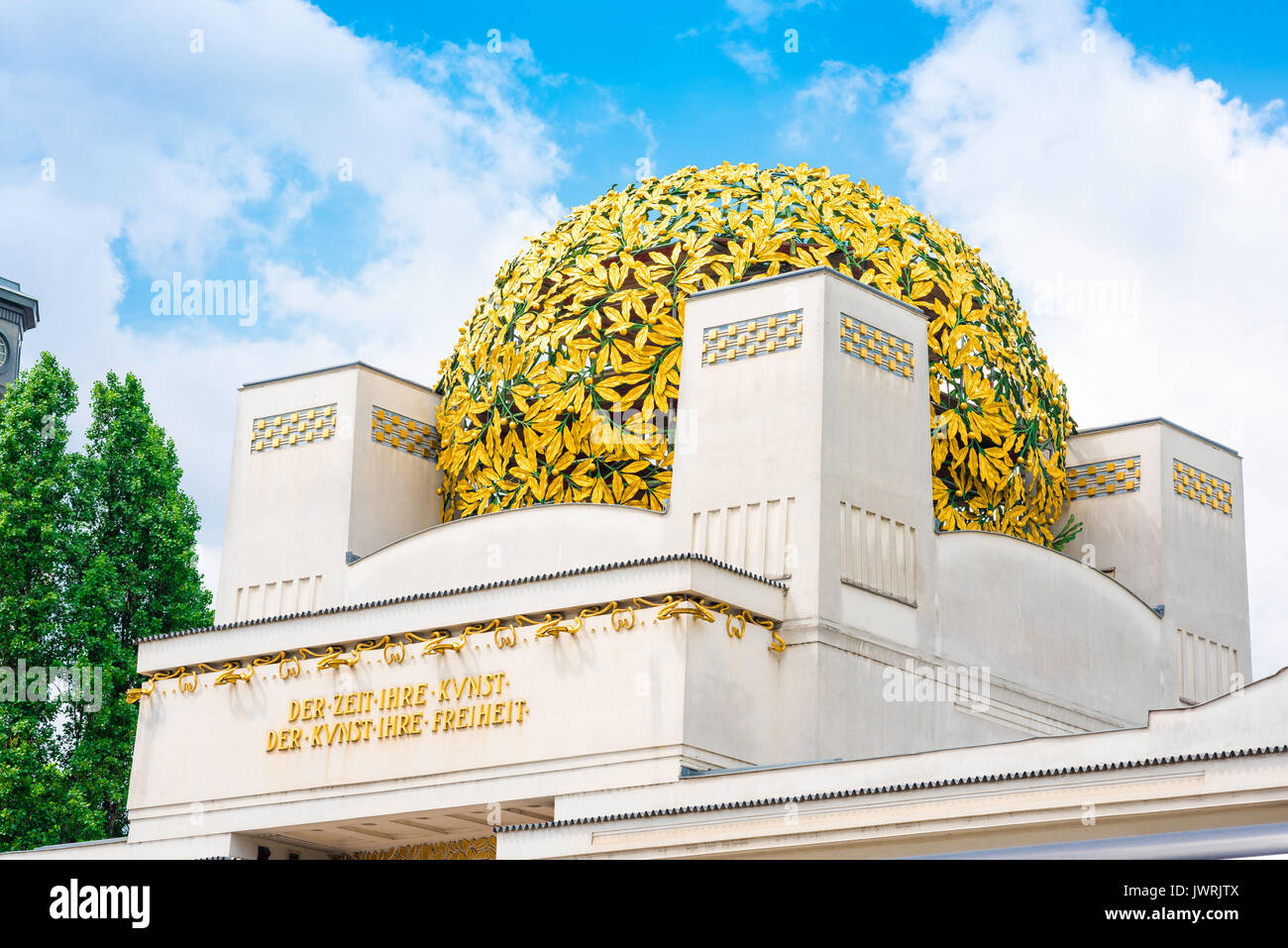

Some 150 color images and 75 black and white archival illustrations make this a sumptuous and historically engrossing study of a period when Vienna was the centre of the European art world.One enters the Vienna show at the Museum of Modern art through a long corridor that seems low-key, even colorless. The book includes eye-witness accounts of exhibitions, the opening of the Secession building and other events, and the result is a fascinating documentary study of the members of an artistic movement which is much admired today. In other fields, Mahler, Freud and Schnitzler were influencing the avant-garde. Klimt, Kokoschka and Schiele were the leading figures in the fine arts Wagner, Olbrich, Loos and Hoffmann in architecture and the applied arts. Art in Vienna, 1898-1918: Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele and their Contemporaries, now published in its 4th edition, brilliantly traces the course of this development. Their work shocked a conservative public, but their successive exhibitions, their magazine Ver Sacrum, and their application to the applied arts and architecture soon brought them an enthusiastic following and wealthy patronage. The artistic stagnation of Vienna at the end of the 19th century was rudely shaken by the artists of the Vienna Secession. Look out for our next story from the Secession, and for a richer understanding of the time buy a copy of Art in Vienna 1898 – 1918 here. We hope you’ve enjoyed this brief overview of the city. To every art its freedom.” By 1900, the Secession had its own journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring) and was establishing an art movement that, unlike the Austrian empire, would last the ages. There was no particular “Secessionist” style, merely an outlook summarised in the slogan inscribed above the Viennese Secession building, “To every age its art. It also placed a great emphasis on applied art, showing how it could impinge on everyday life rather than sit in grand, fusty remoteness.

It was international in outlook, and through its exhibitions brought the French impressionists to Vienna, whose work would itself exercise a significant influence on the Secessionist artists. Now was the time to dispense with artistic precedents and find new ways of presenting art. The Secession was an active riposte to the historicism of the Künstlerhaus and of the academic tradition in general.

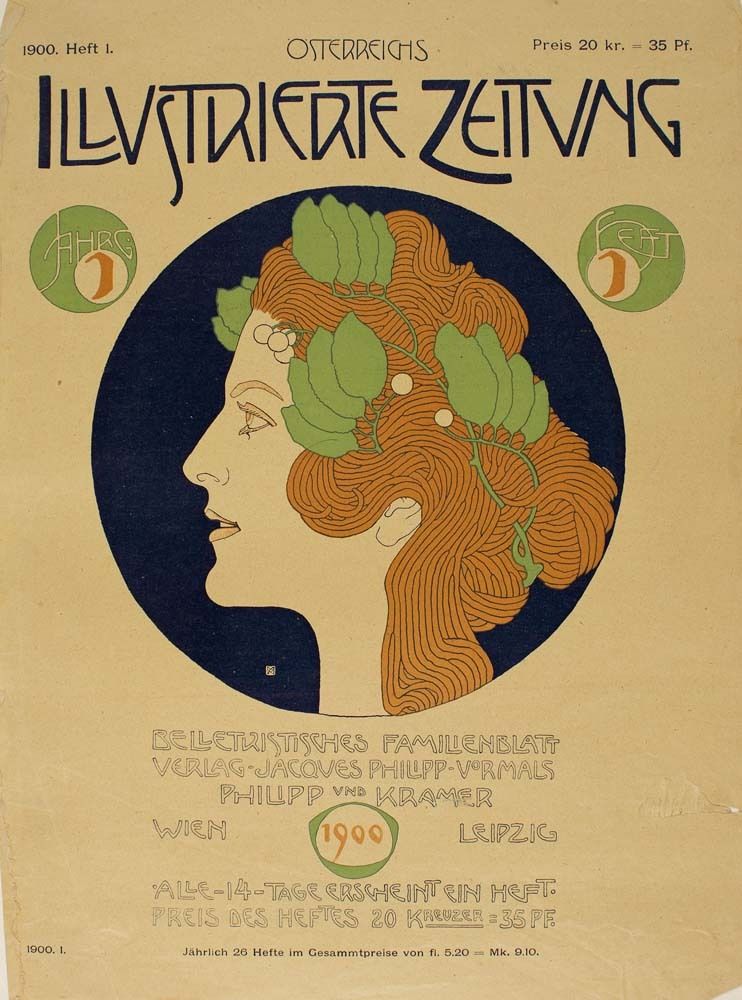

Kolo Moser, poster for the fifth Secession exhibition, 1899

And so it was that in 1897, he and 12 other artists resigned from the Künstlerhaus to form what would become known as the Viennese Secession. The re-election of the ultra-conservative Eugen Felix to the presidency of the Künstlerhaus, the influential exhibiting society threatened the exposure of revolutionary artists like Klimt. It was even actively hostile to the radical developments it hosted, eager to block the galloping progress in the arts. “The slumbering city vegetates in its own mediocrity and does not dream what great things are being thought and created in her midst”, wrote Otto Friedländer.

Meanwhile, 1900 was the year in which fellow Viennese citizen Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation Of Dreams, in which he first introduced his theory of the Oedipus Complex.ĭespite its progressive liberalism, however, Vienna was also deeply conservative and stolidly bureaucratic, oblivious to the impending decline of its thousand-year empire. It was also home to great composers such as Mahler and Schoenberg, who was on the point of revolutionising 20th century classical music with his atonal compositions. Egon Schiele, Death and the Maiden, 1915, oil on canvas, 150.5 x 180 cm (59¼ x 70¾ in) Belvedere, Vienna (© Belvedere, Vienna)Īlthough Vienna was, as the author Robert Musil pointed out, “somewhat smaller than all the world’s largest cities”, at the turn of the 20th century it was the centre of a flourishing and technologically forward looking society in 1899, it had hosted the first ever international automobile race.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)